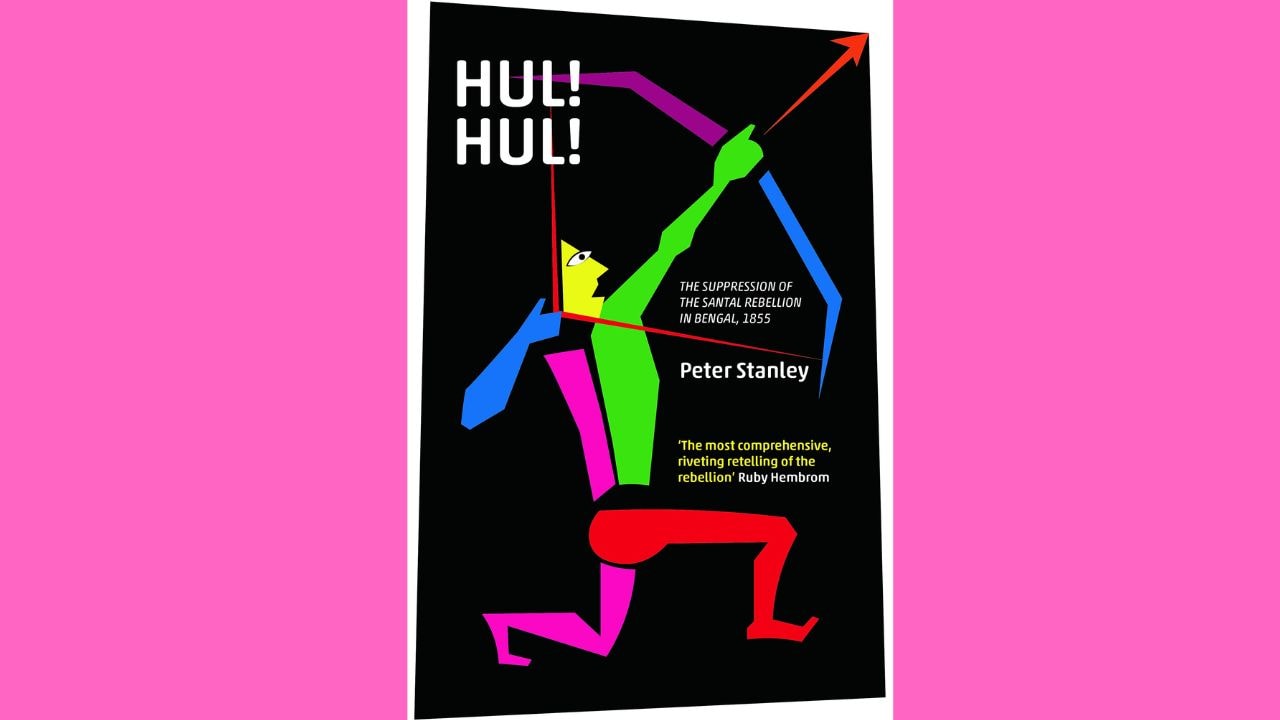

Continuing our patriotic theme for August at Bookstrapping, we take you on a trip back in time, to 1855. Two years before the famous Uprising of 1857, was the not-so-famous Santal Rebellion which rocked the Bengal Presidency.

The Santals were a migrant tribe whose origin was debated – were they connected to Maoris or Persians, was the question. What is known, however, is that in the 18th century they lived by shifting cultivation in the forests of Chota Nagpore. They moved north westward, ‘reclaiming waste land and ousting no man’, reaching ‘Sonthal’ only by the 1830s.

What’s absolutely astonishing about the rebellion of 1855, is that the Santals fought for a region that they were passing through – did it belong to them at all? And yet, the glimpse of their spirit and their travails, provided in the book, is as disturbing as it is enlightening.

1. The Santals used strings – making knots and spaces in them – to keep accounts of their borrowings and debts. Quite novel, except that they were extorted heavily by the Bengal Mahajans (moneylenders). So,if a Santal borrowed Rs 2 and repaid Rs 5, they would still owe the Mahajans the original Rs 2. Believe that if you can! Santal women too were subjected to painful sexual abuse. The Santals also had to pay rent to the Zamindars; overall, they lived in hereditary debt bondage.

2. In order to continue the exploitation, the Mahajans bribed both court officials and police constables. The Santals wondered – ‘to whom should we cry?’ They petitioned the Commissioner of BhagalPore, George Brown, that the Mahajans be removed. Brown did not act on this petition and his extraordinary neglect of duties has been subsequently documented.

3. Pushed to the edge, one of the Santals then proclaimed that a divine deity had appeared before him – what followed was a mix of religion and rebellion – from dacoities to superstitious callings to war. The company officials were taken by surprise, only because they were understaffed and completely unaware of the problems that their ‘subjects’ faced.

4. Faced with loss of control over their own lives, unresponsive Company officials, uncaring landlords and an array of extortionists in various forms, the Santals had absolutely no recourse to justice. They had to rebel or die.

5. Suffice to say that the tribe resorted to armed force deliberately, at the instigation of their own leaders who recognised the cause of their oppression and acted to change their situation. The evidence we have of this rebellion is meagre -there’s the Sidho-Kano national park in Jharkhand – in memory of brothers Sidhu Murmu and Kanhu Murmu, who were the leaders of the Santhal rebellion.

Interestingly, the current President of India, Droupadi Murmu also belongs to the Santali tribe.

In hindsight, the British East India company’s hold over India was the most unusual political phenomenon that ever existed. A handful of Englishmen administered a populace whose culture they knew nothing about, living in places they barely travelled to, with an army of sepoys who belonged to their captive nation! The officers concerned themselves with a ‘revenue number’ that they had to collect – regardless of the inhuman sufferings passed down the administrative chain. Of course, the Indian Mahajans and Zamindars were no better!

Coming back to the Santal rebellion, the British were able to subdue it because they had the experience of quashing the Kol rebellion of 1831-32, which also arose from ‘the evil consequences of introducing into an underdeveloped tribal area, a complex, legalistic administrative system.’

The plot, stratagems and alliances of the rebellion itself, form the bulk of the book. Meet new heroes you probably haven’t heard of and take a moment to be grateful for the freedom we enjoy today. After all, the Santal rebellion was less than 200 years ago!

Reeta Ramamurthy Gupta is a columnist, biographer and bibliophile. She is credited with the internationally acclaimed Red Dot Experiment, a decadal six-nation study on how ‘culture impacts communication.’ On Twitter @OfficialReetaRG